Wat Phra Mahathat has a long, continuing history and many important monuments for various rituals and purposes for people from all walks of life, such as royalties, noblemen, farmers, Thais, Muslim visitors, and foreigners. For the purpose of this nomination, there are 12 main monuments, all of which are in the sanctuary section (Buddhavasa) of the Monastery, except Pho Phra Doem Vihara.

These main monuments and their associated artworks from various periods affirm that this Monastery has been well-maintained through the ages and demonstrate the proposed Outstanding Universal Value (Criteria (ii) and (vi)) and include as follows.

Fig. 2-3 Locations of Main Monuments in Wat Phra Mahathat

- The Great Reliquary Complex

The Great Reliquary complex is the religious heart of Wat Phra Mahathat. It consists of one massive central stupa on a tall, square base, four smaller stupas at the corners of the base, and 120 smaller satellite stupas surrounding the base in three square layers. The sand ground of this complex is around 5.25 meters above sea level.

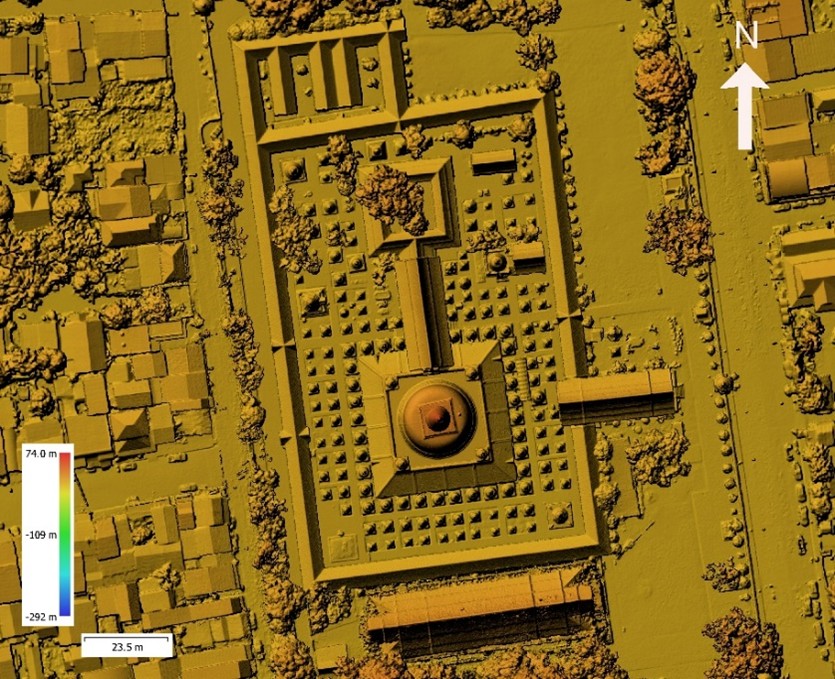

Fig. 2-4 Planview of the Great Reliquary Complex inside the Cloister

For the central stupa where the Buddha’s relics were enshrined, its square base is 29.2 meters wide on each side and 5 meters high. The circular base of the dome is 3.1 meters high and 21.98 meters in diameter, while the dome (anda) itself is 9.8 meters high. The large square platform (throne) between the dome and spire measures 5.30 meters high and the long spire is 20.7 meters high. At the top, the finial remarkably decorated with real gold sheets and jewels is 12.09 meters high. The forms of the four smaller stupas at the corners replicate that of the Great Reliquary in the middle. The top parts of the dome near the square platform have several granite pillars neatly sticking out, which are not apparent in other main stupas in Asia. These curious granite pillars may originally have been architectural parts, such as doorframes and pillars, of older Hindu shrines in the area of Wat Phra Mahathat itself, because these granite architectural parts were common materials of Hindu shrines, but not used in Buddhist buildings in peninsular Thailand. Some of these granite architectural parts are concentrated at the mound, where the newer Buddha’s Footprint Vihara was constructed, in the northern part of Wat Phra Mahathat itself.

Fig. 2-5 The Great Reliquary and Corner Stupas

Fig. 2-6 The Satellite Stupas

Fig. 2-7 The Great Reliquary’s Platform and Granite Pillars

The Great Reliquary was constructed under the architectural influences from India and Indonesia (central Java). The layout of this large complex was thoughtfully designed to three-dimensionally represent the mandala (the cosmic diagram of the sacred universe), in which there are three horizontal, square layers of smaller, satellite stupas surrounding the large square base of the Great Reliquary. Approximately, a stupa in the innermost layer is 9.98 meters high and its square base is 3.75 meters wide. A stupa in the middle layer is 7.95 meters high and its square base is 2.95 meters wide. A stupa in the outermost layer is 7 meters high and its square base is 2.25 meters wide. The height of these satellite stupas decreases progressively from the innermost to the outermost ones, arranged symmetrically and orderly along an axis radiating from the central stupa, creating a remarkable visual appearance of the spiritual ascent to the upper realm.

The scientific dates from the archaeological excavation at the foundations of the Great Reliquary and satellite stupas suggest that they were probably first constructed around the late 8th to early 10th centuries. The Fine Arts Department excavated right at the square base of the Great Reliquary and found several courses of large bricks arranged neatly, one on top of the other. Some complete bricks are as big as 28x40x10 cm., comparable to those of early historic sites in Southeast Asia. Brick samples from the very organized lower brick courses from Test Pits at the base of the Great Reliquary were collected for Thermoluminescence (TL) and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating at various labs. Most of the dating results were quite consistent. The majority of TL dates include CE 764-898, 780-892, 788-918, 822-930, and 836-942, while an AMS date is CE 850-910. These dates correspond well with the scientific dates from the archaeological excavation at the foundations of satellite stupas as follows: all TL dates here include CE 878-980 and 839-965 and AMS dates consist of CE 775-790 and 800-980 (Ueasaman 2022:211-218). Therefore, it is most likely that the Great Reliquary and its satellite stupas were constructed at the same time in a mandala layout around the late 8th to early 10th centuries.

This type of mandala layout was used in Hindu architecture and more often in Mahayana Buddhist architectural arrangement, characteristically appearing in the Mahayana temple layouts in central Java (Indonesia) around the 8th-9th centuries, such as those of the Borobudur, Sewu, and Plaosan temples, and at Khao Klang Nok Temple (Si Thep, upper central Thailand). A very few Hindu temples adopted this mandala layout, such as Prambanan Temple (central Java) from the 9th century and Phnom Bakheng Temple (Angkor, Cambodia) from around the end of 8th century. It is evident that this architectural mandala layout was most popular in central Java. All temples mentioned above are defunct. This fact makes the Great Reliquary complex of still vibrant Wat Phra Mahathat the longest living example of this particular mandala layout in maritime Asia.

The link between central Java and Nakhon Si Thammarat is also supported by Inscription No. 23, also called the Ligor inscription, found at Wat Sema Mueang located just 1.5 km north of Wat Phra Mahathat. Written in Sanskrit with modified Pallava script, its Side B (called Ligor B) mentions the ruler probably named Vishnu of the Sailendras, the dynasty from central Java, and may be palaeographically dated to the late 9th century, according to Hermann Kulke (2016), while Side A (called Ligor A) has a date of 775 and mentions the ruler of Srivijaya, a prominent confederacy in maritime Southeast Asia, which had extensive trading and Mahayana religious connections.

Wat Phra Mahathat’s Great Reliquary has a tall square base with one staircase to the north. On top of the tall base, the Great Reliquary is in the middle and there are four smaller stupas of the same style located at each corner, altogether forming a sacred quincunxial arrangement, akin to Stupa No. 3 at Nalanda in India. The dome of the Great Reliquary is of a stout, tubular bell shape, different from the dome shape of Sri Lankan and Pyu (in Myanmar) stupas, but akin to that of the Pala art of northeastern India, such as the stupas at Nalanda, from the 8th century, which also influenced the style of stupas at the Borobudur and Sewu temples. However, the Great Reliquary has the largest surviving dome among all stupas of this particular type in Southeast Asia, attesting to the universal significance of this property. The Great Reliquary’s tubular dome shape also inspired other monasteries in peninsular Thailand, such as the Khian Bang Kaeo, Phako, and Phra Boromathat Sawe monasteries.

Fig. 2-8 Main Stupa of Khian Bang Kaeo Monastery, Phatthalung Province

Fig 2-9 Main Stupa of Phako Monastery, Songkhla Province

Fig. 2-10 Main Stupa of Phra Boromathat Sawe Monastery, Chumphon Province

In circa the 12th-13th centuries, the Great Reliquary’s platform between the dome and spire was probably modified to a Sri Lankan large, square type, such as those in Polonnaruwa. New Digital Surface Model (DSM) images, taken with a drone using the photogrammetry technique, further supports this hypothesis. The images show that the square shape of the platform between the dome and spire is tilted off and not aligned with that of the base of the Great Reliquary, indicating that they were likely not built at the same time. The original Pala-style platform, which is usually proportionately narrow with indented corners, from the late 8th-early 10th centuries was probably rebuilt to a large square one in Sri Lankan-style in the 12th-13th centuries, and in a later period, this platform was beautifully adorned with Chinese porcelains, demonstrating the extensive maritime trade network of Nakhon Si Thammarat.

Fig. 2-11 Digital Surface Model (DSM) Image of the Great Reliquary Complex

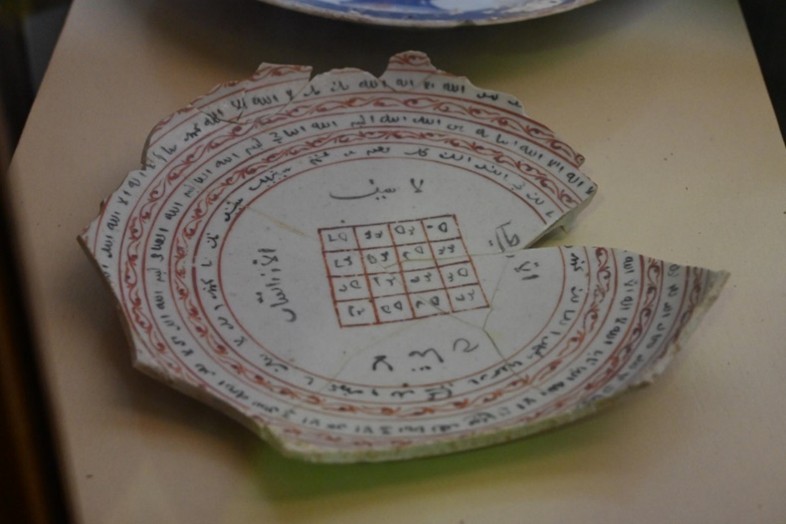

Fig. 2-12 Fragment of Chinese Qing-Dynasty Ceramic (c. 17th-18th centuries) with Arabic Writing, Once Adorning the Great Reliquary

The niches of elephant statues around the square base of the Great Reliquary were probably added in c. the 12th-13th centuries in Sri Lankan style, although there is also a possibility that there were original features from the late 8th-early 10th centuries. A notable example of elephant statues around a stupa’s base from Sri Lanka includes Ruwanwelisaya Stupa in Anuradhapura which was renovated by King Parakramabahu I (1153-1186 CE) of the Polonnaruwa kingdom.

The art historical date of this major renovation coincides with the TL dates from the archaeological excavation at the base (next to an elephant niche) of the Great Reliquary. The TL dates of several upper layers of bricks include CE 1015-1119, 1028-1120, 1023-1125, 1055-1145, 1071-1163, 1084-1178, and 1237-1305; the last date is from the topmost brick layer in the excavation). Additionally, there are also some broken bricks on top of the neat brick layers in the excavation. They give the TL dates of CE 1455-1503, 1458-1504, and 1459-1505. This data indicates that the major renovations of the Great Reliquary and its circumambulation path around its base took place around the 11th-12th centuries, the 13th century, and the latter half of the 15th century, suggesting that this living complex have been well-maintained and preserved through the ages.

The Mon architectural elements also influenced the style of the Great Reliquary in circa the 15th-17th centuries, such as the decoration of the finial of the Great Reliquary with real gold, which was not present in Sri Lanka. The local chronicles of Nakhon Si Thammarat also mentioned that its first king, who supported Theravada Buddhism, came from Hamsavati, a capital of the ancient Mon country in southern Myanmar. A famous Mon-influenced stupa in Yangon, southern Myanmar, with gold finial includes Shwedagon Pagoda, whose present form can be dated to the 15th century.

Fig. 2-13 The Niches of Elephant Statues around the Great Reliquary’s Base

Fig. 2-14 The Gold Finial of the Great Reliquary

The Great Reliquary’s finial continued to be embellished throughout the Ayutthaya period with gold and jewelry in various years, notably in CE 1612, 1649, 1670, 1686, 1687, 1688, 1692, 1699, and 1734. In subsequent periods, specifically the Thonburi and Rattanakosin (Bangkok) periods, the maintenance of the finial with gold and personal valuables, such as rings, showing people’s intimate devotion to the Great Reliquary, took place intermittently and extends into the present day. Impressively, the total real gold sheets currently weigh 197.45 kilograms. The gold and valuables for this purpose has been donated by a diverse array of benefactors, including monks, laypeople, royalties, and nobles. Notably, each gold sheet is inscribed in Thai. These inscriptions typically include the names and domiciles of the donors, the date of the donation, the weight of the gold, and the donors' highest wishes. Common wishes inscribed include the attainment of the three treasures: human treasures, heavenly treasures, and nirvana treasures, as well as the aspiration to meet Bodhisattva Maitreya, demonstrating the syncretism between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. This golden finial gives the Great Reliquary its grandest, most unique character, making it one of the most recognizable living stupas in Southeast Asia.

As the centerpiece of Wat Phra Mahathat, the Great Reliquary complex is the spiritual core of diverse, deep-rooted, living traditions, which are associated with indigenous beliefs, Hinduism, and Buddhism, all syncretizing together. These living traditions of outstanding universal significance include, for example, the tenth-month ancestor worship, the annual cloth wrapping ceremony for the Great Reliquary, the Nora dance, and the unique chanting of Nakhon Si Thammarat chronicles at Wat Phra Mahathat.